24/05/21

The Driven

The International Energy Agency has made it abundantly clear: If the world is to achieve its climate target of capping average global warming to 1.5°C, the sale of new petrol and diesel cars needs to stop by 2035.

Some countries, such as Norway and the UK, have already legislated to ban sales of ICE cars by that time, or even well before. But could Australia, currently trailing the world in the uptake of EVs with a miserable one per cent of total new car sales, also meet that target?

Many would say no. And some companies, like petrol refiner Ampol, are counting on it. In its new “status quo” business modelling, it assumes that the penetration of electric cars remains at just one per cent 2030. In its “2°C” modelling, the share of EVs reaches 13 per cent, but Ampol gets to sell petrol well into the second half of the century.

It might want to rethink those assumptions, and its business model – despite sharing in the newly announced $2.3 billion subsidy from the federal Coalition government to the oil industry to keep its last two Australian refineries open.

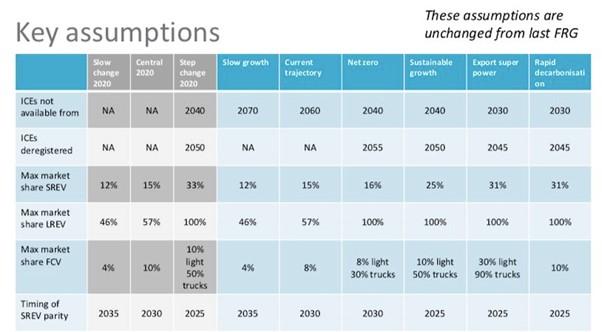

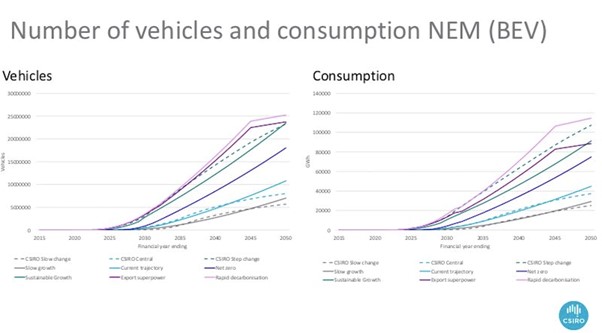

A series of scenarios presented by the CSIRO in late March presents a completely different picture. It outlines a range of different scenarios for the uptake of EVs, and the implications these might have on electricity consumption and the operations of the grid.

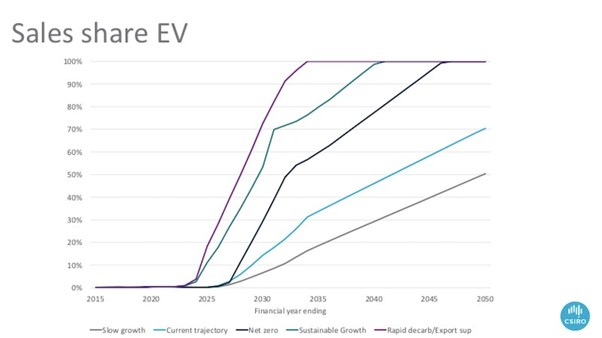

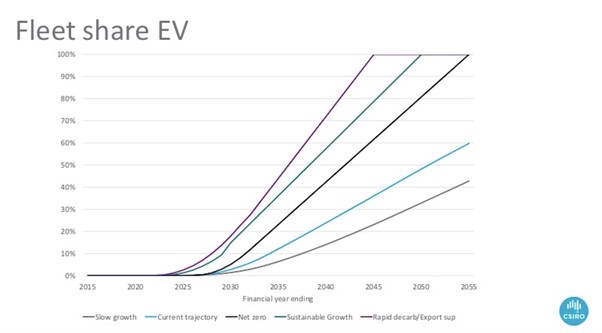

But there are two standout conclusions from the modelling. The first is that Australia could – under the “pull effect” of net-zero policies and the “push effect” of a global car manufacturer switch to EVs – could reach zero new car sales of petrol and diesel cars by 2035 (graph above) and have virtually none on the road by the mid 2040s (graph below).

It is important to note that these are not predictions but modelled scenarios, were requested by the Australian Energy Market Operator to help it prepare its latest 20-year planning blueprint, known as the Integrated System Plan.

CSIRO economist Paul Graham tells The Driven that the uptake forecasts are significantly quicker than previous modelling. It is driven by a lot stronger emphasis on net zero policy outcomes, and the increased focus on the 1.5°C target now widely embraced by global bodies such as the UN and the G7.

That, says Graham, is the policy pull. Then there is the “push” from the global car making industry, within which many are promising to make electric cars only from the early 2030s.

“There might be a future when we stop manufacturing internal combustion vehicles,” Graham says. “You put those two things together and you got a lot stronger predictions on the uptake of EVs than in previous years.”

The graph above provides more detail of what various policy decisions might mean for Autralia’s EV uptake over the next few decades. Net zero means no new ICE vehicle sales from 2040, but the export superpower and rapid decarbonisation scenarios show the transition complete in 2030 after price parity is reached in 2025.

It is unlikely that the current federal government will entertain such policies, but it is very likely that international car makers will stop making new ICE vehicles for major markets, which will either turn Australia into a dumping ground for dirty engines, or finally provoke a policy response based on market reality.

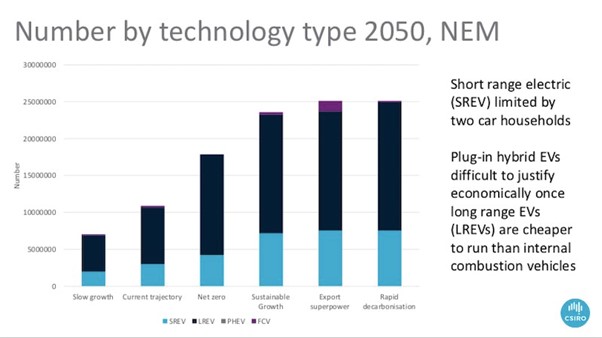

Importantly, having this number of EVs on the road – nearly 25 million by the mid 2040s – will have an impact on the grid. The CSIRO analysis suggests consumpion of 120,000 gigawatt hours by the mid 2040s – more than half total annual grid demand in Australia. That will require a lot more wind and solar and storage.

Subscribe to our free mailing list and always be the first to receive the latest news and updates.