The Australian

February 2, 2017

ROWAN CALLICK

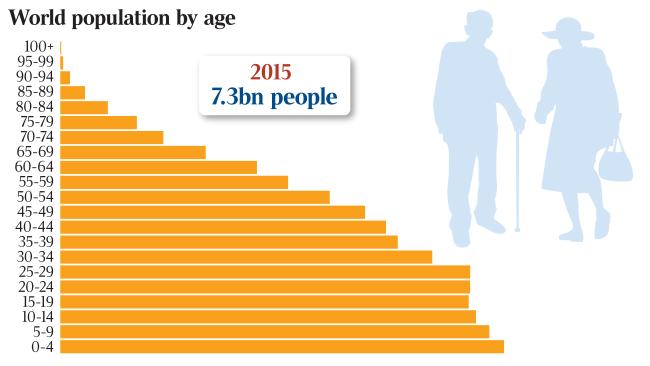

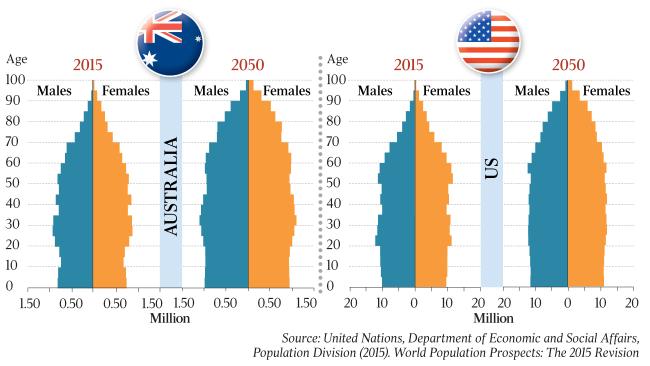

Australia is among those affluent countries — Western and north Asian — that are entering the age of the old.

This is usually viewed as a matter of grave concern, especially by business advisers who tell companies they must focus on youthful markets. However, if viewed from a demographic perspective, this trend also presents some massive opportunities for developed economies — for companies as well as for individuals.

Clint Laurent, a New Zealander with a doctorate in econometrics and marketing, founded and runs Global Demographics, whose clients are mostly Fortune 500 companies. The company has offices in Hong Kong and Britain.

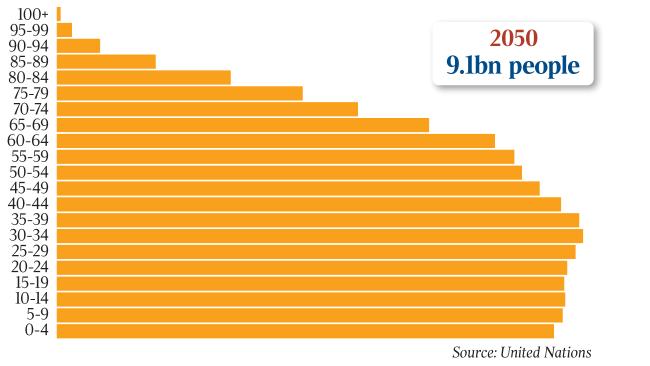

His message to them is that the under-35 age group is not growing anywhere in the world except in sub-Saharan Africa. Even in India the only age group that is growing is 35-50. “So if you have a brand and are wanting to grow your market, you would look at products appealing to the 35-year-old head of a family, not to 25-year-olds,” he says.

But, he points out, investment banks continue to advise clients to reconsider or simply stop investing in societies — including Germany, South Korea and Japan — where the working-age population is climbing. A big mistake, he stresses.

Closer to home, the median age of the population rose by three years over the 20 years to 2016, but remained stable over the last of those years.

Tasmania experienced the largest increase. Its median age was up seven years to 42 in 2016, followed by South Australia’s 40 years. The Northern Territory had the youngest median age, 33 years, followed by the Australian Capital Territory with 35.

This is the result, the Australian Bureau of Statistics says, of sustained low fertility and increasing life expectancy, resulting in proportionally fewer children in the population and a proportionally larger increase in those aged 65 years and over.

During the past two decades, the proportion of people aged 65 years and over increased from 12 per cent to 15.3 per cent and the proportion of people aged 85 years and over almost doubled to 2 per cent. The cohort over 65 is projected to increase more rapidly over the next decade, as more baby boomers reach that age.

But as Penny O’Donnell, a senior lecturer in international media and journalism at Sydney University, wrote in a book on media innovation and disruption, “there has been an explosion in online media outlets aimed at younger audiences”. “Market analysts tell us Big Media are chasing 16 to 30- year-olds with purchasing power,” she says.

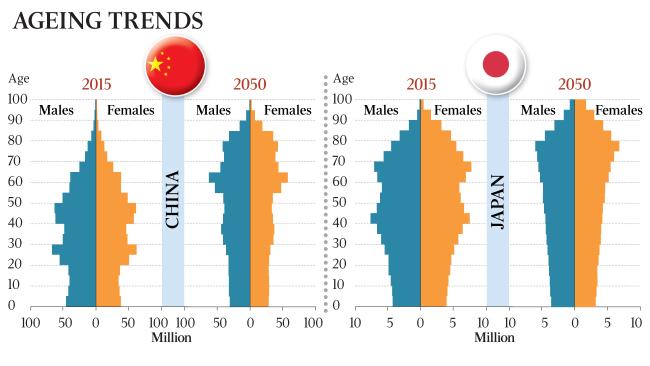

In China too, Laurent says, “everyone is chasing the youth market”.

The one-child policy has been relaxed now but it will take 14 years for that change to produce sufficient youngsters to match the opportunity now emerging in the older age group.

Education and affluence change attitudes, he says. Already 25 per cent of those in China who have been eligible for some years to have a second child have chosen not to do so, and he expects that rate to rise to 40 per cent.

In stark contrast to popular opinion, which routinely writes Japan off because of its ageing profile, Laurent says: “We are really bullish about Japan.”

Last year, 24 per cent of Japanese men aged 70 to 74 were in full employment. In the US, it’s 21 per cent, in Britain it’s 23 per cent and in Germany it’s 22 per cent.

“Everyone is overlooking that life expectancy has reached 84 or 85. They may suffer pension insecurity but they don’t want to sit down doing nothing for the next couple of decades after they retire,” Laurent says.

“Companies are discovering that it’s a damn sight cheaper to keep someone on and develop their skills and build on their knowledge of the company structure than to hire a young buck who is only going to stay a couple of years then move on.

“That’s a growing trend and suddenly you find in Japan a dependency rate of 1.08 dependants per worker — which is not going to increase for the next decade. That’s very low by world standards. In India, it’s 1.74.”

Including western Europe, North America and affluent Asia, the proportion of the workforce over 65 has reached 13 per cent.

Laurent, who began working at Hong Kong University in the days of mainframe computers — of which at first the university had just one — said that since no one else seemed interested in commercialising statistical analysis, he started to sell market insights he obtained from data.

“It was hard going at first, taking eight years to start turning a profit. But now his firm’s take on trends is becoming established as a core component for corporate planners,” he says.

China was a particular focus, naturally from a Hong Kong base but also because “it was the only country where everyone was documented, and government information was available to us” through the National Statistics Office. “So we can’t get arrested for revealing state secrets. And our cost of inputs is almost free.”

Global Demographics’ interactive model includes the birthrates and death rates that projections might be based on, so clients can check out how a society looks if, for instance, the forecast is shifted forward a year.

“Very few people are interested in looking more than 10 years ahead — most, inside five years. But really big changes are often insidious,” he says, they creep up.

For example, China’s 15-to-25 age group is declining but the 45 to 64 group, many of whom have urbanised, is growing fast. There are now 300 million in this category, many of them working people who are empty-nesters. In 10 years, there will be 400 million in this category. Most of those working in the age range are male.

Household costs in that group are down by 50 per cent per person, he says, with their child leaving home, the apartment has often been paid for and there are no more education costs.

“They are saving for pensions and for health costs, but they are spending more also on other items, including travel and media consumption. Not necessarily more clothes or food, Laurent says, “but better”. They eat out more often at a restaurant.

“You can argue around gross domestic product numbers,” he says, “but age changes are inevitable. The only question is, how much will incomes rise. Some are growing at very high compound rates in China, thus real household incomes and spending power are also growing rapidly.”

Income rises of more than 10 per cent per year are common in this group — boosting the consumer market by that amount.

The western European economies are in quite good shape, he says, but eastern Europe could be doing better because it has a comparatively well-educated workforce but it is losing these people — Poland, for instance, 1.7 per cent per year — to migration, often of the better skilled. “Free movement of labour is damaging their ability to grow,” Laurent says.

A reason that Japan is looking especially positive, he says, is because it has the fastest growing female work participation rate in the world, albeit off a low base.

“This is driven by women aged 45 and above whose children have finally left home and are tired of being a Japanese housewife. This woman is smart too. Japan has always had equal education outcomes by gender. Twenty five years earlier they would have been told to stay at home. Times have changed.”

South Korea’s female participation hasn’t picked up the same impetus. Nor, for instance, has Malaysia’s or Indonesia’s — where it stands at about 45 per cent, perhaps influenced by religious imperatives. In China and Vietnam, though, it has reached 70 per cent.

Life expectation is also changing labour force profiles. In China today, Laurent says, a 50-year-old male is likely to be dead by 72. “But improved healthcare and nutrition will change that.”

The generation that has made the transition from rural to urban living suffers more, he points out, from pollution and from hypertension — with half of urban males in China suffering from the latter, while many cannot afford the statins to suppress it.

“So the older workforce there is only increasing marginally. Thailand has a similar scenario. Taiwan and Hong Kong have workforce profiles a bit more like Europe, though — older but quite affluent. They’re in quite good shape.”

Laurent is telling his corporate clients: “Forget this emerging market stuff and look at the wealthy countries of North America, affluent Asia and western Europe.

“We look at where dollars are being spent in the world today, except in sub-Saharan Africa, where there is no data.

“Most of those countries have no census. The last in Zimbabwe was in 1971. You can’t do anything in terms of market analysis without data.

“We can say for certain that of every dollar spent, 66 cents are being spent in those three wealthy areas, although they have just 18 per cent of the global population.

“So if you are a manufacturer, where do you go?”

Some companies like Unilever, he says, sell everywhere. People buy shampoo, for instance, almost everywhere. But often there’s virtually no profit in such sales. “You have to be selling to households with income of more than $US20,000 ($26,000) to make a profit.”

Forget measuring an economy by purchasing power parity — comparing a basket of goods across countries, he says. “That’s just a fudge. What matters is hard cash. China’s consumer spend is growing 6 per cent this year, even Britain’s is growing 1.7 per cent.

“The size of household income matters immensely. Yet investment bank people focus obsessively on growth rates. It’s sanity versus vanity.

“A country like Japan is bound to keep growing. Business opportunities are profitable because margins are good, and you can get your profits out. Consumption typically comprises 65 per cent to 70 per cent of GDP in a developed country. In China, it’s 45 per cent.”

Thus Japan’s consumer market, he says, is not that much smaller than China’s but is of course a larger proportion of GDP.

Increasingly, he says, while fund managers claim to be taking a medium to long-term view, their conclusions fail to reflect appropriate research. “Often you’ll hear them say things like Japan is running out of workers. It makes them look ignorant.”

Countries are discovering, he says, that more people are not necessarily a good thing. “Japan is shrinking, but in a planned manner. That is a model China is looking at. Having fewer people who are more affluent means a better lifestyle. And robots are coming in.”

Overall, he says, “you have to admire China. It has its faults. But it has few children, and it gives them good opportunities to improve themselves.

“There are now four million Chinese living in households with annual income of more than $US125,000, growing to about 30 million in 10 years.

“They won’t be feeling they need to buy to display their wealth. Quality food, wellness and tourism will be big spending areas for them.

“As a whole, north Asia is now not really different from North America or Europe” in its wealth profile. Southeast Asia also has great growth prospects, Laurent says. “This part of the world provides a brilliant opportunity for Australia.”

Subscribe to our free mailing list and always be the first to receive the latest news and updates.