In the main committee room of Parliament House, Labor MP Jerome Laxale held up a crumpled $5 polymer banknote. Why, he asked the bosses of Australia’s major banks, if he paid for the same cup of coffee with his debit card did it cost $5.08?

He produced a debit card with the inflated price taped to its front to ram home the apparent injustice, like a referee wielding a red card.

It was a simple question, and one that is being asked all over the country.

Tap-and-go debit card surcharges have become a political firestorm. Robert Duong

When a $40 round of drinks shows up on an electronic payment terminal as $40.64, nobody can say precisely where the 64¢ goes.

And when these charges are aggregated across the economy, the cents add up to big dollars.

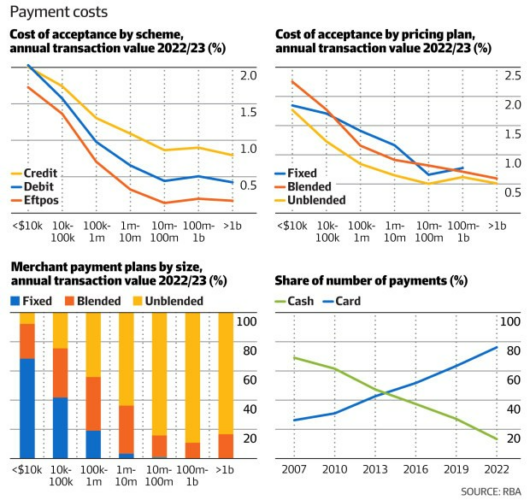

Australians spend $1 trillion on credit and debit cards annually, racking up 15 billion electronic payments. To sustain the system, banks and payments companies charge businesses about $7 billion in annual fees, according to industry estimates.

Unlike ordinary business costs, such as keeping fridges cold or even accepting cash, a merchant can pass their digital payment costs on to customers because of a controversial Reserve Bank rule now under review.

Some retailers have been taking advantage of this loophole, pocketing more than the cost of acceptance and flouting rules set by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, which is also monitoring the area.

Assuming 10 per cent of the economy’s transactions (the actual number is unknown, even by the RBA) are surcharged at 1.5 per cent, Australians are slugged $1.5 billion annually in opaque payment fees.

Canstar came up with an even higher estimate: $4 billion, the number cited by Laxale in his speech to parliament the previous week where he described the “kickbacks” as a “rort”.

The theatrics rattled the bank chiefs.

“It’s a false comparison,” Commonwealth Bank chief executive Matt Comyn told the House economics committee.

CBA chief Matt Comyn, in Canberra last week, explained the quirks of surcharging. Alex Ellinghausen

Comyn explained that when Laxale paid with the banknote, the costs related to handling his cash were embedded in the price. Banks have never charged customers – at least directly – for transacting in cash.

Indeed, before the Hayne royal commission, banks eliminated ATM fees, helping to condition people to think cash is free, despite growing costs (to banks) of circulating it through the economy.

Boston Consulting Group, in a report published last week, estimated thataccepting cash actually costs twice as much as digital payments.

In fact, Australia is among the lowest-cost jurisdictions in the world for digital payments, and Comyn told the committee that CBA’s merchant terminal business was losing money.

But because of the ability to surcharge, these costs are visible, leading politicians to question whether they are appropriate despite extensive regulation.

Payment revenue earned from merchants is shared between banks that issue cards to the consumer (interchange fees which are about 30 per cent of the direct cost), the network providers Visa, Mastercard and Eftpos (scheme fees, about 20 per cent), and the banks that supply the physical terminal to the retailer (the acquirer margin, representing about half the cost).

Over the past fortnight, the complex area has become a new flashpoint, eliciting rebukes from Canberra and adding fuel to the fire of populist politics.

One Nation is circulating a video on Facebook depicting Prime Minister Anthony Albanese being surcharged by cigar-smoking bank bosses when buying a sausage at Bunnings.

Bank CEOs say they understand the frustration.

National Australia Bank chief executive Andrew Irvine told Laxale it was “outrageous” he was forced to pay $5.50 for a $5 coffee in Sydney.

At NAB’s head office in Melbourne’s Docklands, a $4.50 flat white costs $4.57.

The ACCC has been writing to businesses it believes are going too far with surcharges, warning of potential regulatory action if costs exceed actual fees incurred.

Labor MP Jerome Laxale brought props to the House standing committee on economics last week.

“It is confusing customers,” Westpac CEO Peter King agreed.

“We really have to think about whether surcharging is worth it because I’m not sure if it’s driving the policy intent … There’s no other cost in a business that people get to surcharge.”

When surcharging was introduced 20 years ago, the RBA put Australia out of step with most of the rest of the world, where the practice is illegal.

But the central bank’s intention was reasonable: surcharging was designed as a price signal to customers that the more expensive payment methods at the time – credit cards – were a burden for the seller.

Lately, banks and fintechs have introduced fixed pricing plans in an attempt to reduce payment fee complexity for business customers.

These plans let a merchant pay the same cost irrespective of what card the customer uses.

But this has resulted in more surcharging of debit cards, another of Laxale’s frustrations.

The brewing firestorm has forced the RBA to review merchant payment costs and surcharging; a consultation paper is being prepared and due to be completed by the end of the year.

The review will hear underlying concerns about fairness.

Small businesses will argue they are paying a disproportionately high amount of the fees because large retailers like the supermarkets get better deals.

Baby Boomers are using credit cards more often, and benefiting from their rewards at the expense of their kids.

— Warwick Ponder, Independent Payments Network

And debit card users are coming to realise that blended pricing involves cross subsidisation of credit cards loaded with benefits such as rewards points that they don’t participate in.

Another way of putting it is young people on debit schemes are making it easier for older Australians to support their frequent flyer habits.

“Eighteen- to 29-year-olds now make almost 80 per cent of their transactions on debit cards,” says Warwick Ponder, from the Independent Payments Network, which is representing small business groups on the issue.

“At the same time, under these pricing constructs, Baby Boomers are using credit cards more often, and benefiting from their rewards at the expense of their kids,” he says.

“Unfortunately, that means the people who can least afford it, like Millennials, Gen Zs and low-income earners, are paying for credit risk and services they don’t get.”

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

The RBA estimates that the average wholesale costs of processing an Eftpos payment, which uses a domestic network, is less than 0.5 per cent.

Costs are between 0.5 per cent and 1 per cent for the Visa and Mastercard debit networks, and between 1 per cent and 1.5 per cent for Visa and Mastercard credit. American Express charges 2 per cent.

The fees are spent on maintaining the network, its security, and services that the popular debate often overlooks: compensating merchants for fraud, and refunding customers if goods are not delivered.

Credit cards are more expensive because banks buy rewards points from airlines to use as sweeteners, with the objective of facilitating more transactions to earn higher interest from borrowers.

Surcharging goes rogue.

But the rise of fixed, or blended, price plans has created its own maelstrom.

The new pricing structures were introduced by Square, part of Block, when it entered the merchant market in 2016 with a competitive price of 1.6 per cent.

This helped it lure cafes and restaurants off bank terminals and forced the major banks to follow: CBA charged a fixed 1.1 per cent; the other major banks slightly higher.

A perverse outcome of simpler pricing is it is resulting in many small businesses being charged more than the wholesale cost of Eftpos transactions, which are supposed to be cheaper.

And by allowing the banks to decide which transactions rout between Eftpos and the international schemes, fixed pricing plans are rubbing up against another RBA payments tenet known as “least-cost routing”.

This is supposed to allow merchants to choose to send payments to the lowest-cost network.

Whether banks are booking extra profit through Eftpos and withholding this from merchants will be investigated by the RBA.

After more than an hour of questioning Australia’s big four, Laxale says he remains concerned.

“I’m still no clearer why cash costs are embedded but Eftpos debits aren’t, particularly when Eftpos debit is owned by all banks and retailers,” he says (this is true).

“My argument is we should have one fee-free digital option.”

The RBA will be forced to respond.

One option supported by the banks is banning surcharging.

But this will create blowback from small business groups, whose members are struggling under an inflation outbreak and want to retain the right to recover card payment charges.

A surcharge ban would be utterly devastating to the restaurant and cafe segment of the accommodation and food service industry,” says Wes Lambert, CEO of the Australian Restaurant and Cafe Association.

“With some venues facing up to a 50 per cent drop in net profit if a ban is introduced, they will need to put up menu prices to cover the merchant fees they must pay leading to further inflation.”

The RBA could consider restricting surcharges on debit, while still allowing retailers to pass through a credit card fee. The fixed or blended pricing model could be broken apart.

The central bank may consider tougher regulation of fees, too.

This could include reducing the 0.2 per cent cap on debit interchange fees, or lowering the 0.8 per cent cap on credit card interchange, in line with Europe, where it is 0.3 per cent.

Retailers are suggesting domestic Eftpos debit transactions be capped at zero cost for transactions less than $50.

It’s an area that also needs more transparency: payment terminals could show true surcharge costs before a transaction goes through, like at ATMs.

Yet this would slow down the tap and go experience and involve large technology investment.

Another idea could involve the RBA forcing banks and payment providers to publish comparable disclosures ranking them on the wholesale cost for acceptance, including fees paid to the international schemes.

View article source here.

Subscribe to our free mailing list and always be the first to receive the latest news and updates.